AI accelerates this urgency but doesn’t change the fundamentals. The winning pattern is a shared toolbox with clear standards and autonomy at the point of value creation, a more precise form of control.

It rarely begins as a strategic debate. More often, it starts as a moment of frustration.

A regional team has missed another opportunity. A campaign that should have taken weeks has taken months, not because the idea was unsound, but because the organization could not move quickly enough to act on it. Nothing radical was requested. The change was modest. The urgency was real.

The response, however, is familiar. Other markets must be considered. The request needs to move through the global backlog. It will be prioritized in a future planning cycle.

No one in that exchange is wrong. The global team is doing what it was designed to do, and the local team is reacting to real commercial pressure. Yet no one leaves the conversation with greater confidence in the system. While this discussion repeats itself, a second conversation is taking place elsewhere in the organization. AI has moved firmly onto the board agenda, raising questions about readiness, data, accountability, and whether the current operating model can support what comes next. Gradually, these conversations begin to converge.

(Research from BCG Insights suggests that successful digital transformations follow a strict ratio: 10% effort on algorithms, 20% on data/tech, and 70% on business process and people transformation. If your operating model hasn’t evolved, you are likely neglecting the 70% required for success).

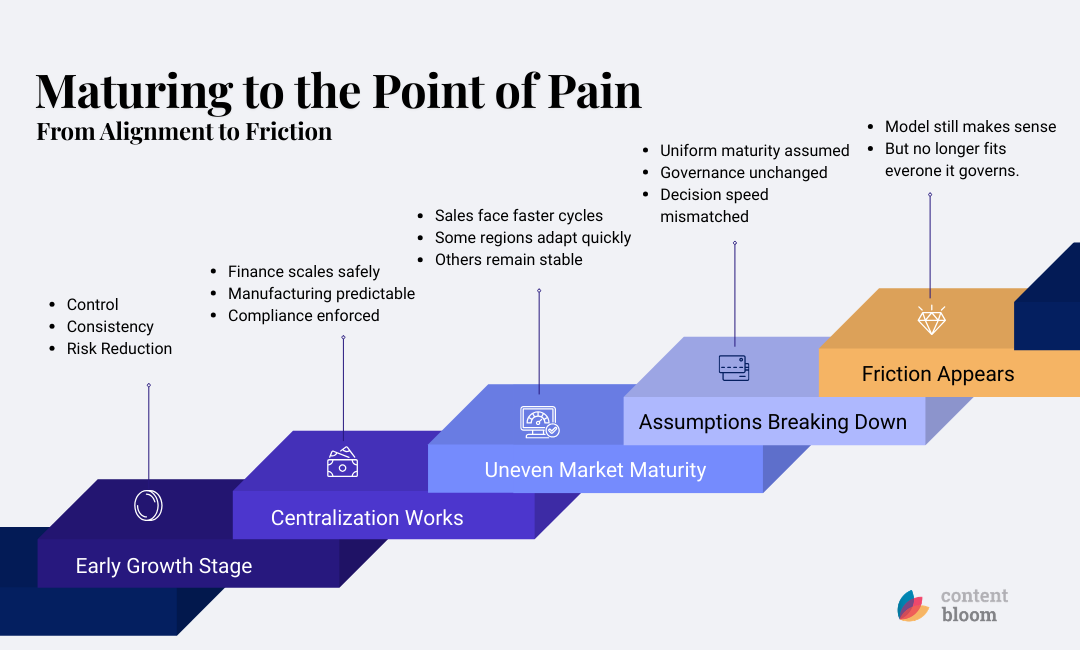

What emerges is not disagreement, but tension. A model that once brought order and control is now being asked to serve a business that no longer behaves uniformly. Most organizations experience this tension long before they have the language to describe it.

For much of the last decade, centralization was the right response. Digital estates had become fragmented and inefficient. Too many platforms, too many agencies, overlapping capabilities, and inconsistent standards made scale difficult and risk hard to manage. Centralizing technology, governance, and brand created stability where it was badly needed. Costs reduced, consistency improved, and digital became manageable again. That logic remains sound, and it still applies in many parts of the value chain.

This is what it means to mature to the point of pain.

Finance depends on central control. Manufacturing requires it. Product development, regulatory compliance, and data protection cannot function without clearly defined, centrally owned standards. These areas must scale safely and predictably, and there is little debate about that.

Selling, however, operates differently. Marketing operates differently. Customer expectations, competitive pressure, and routes to value now vary far more than they once did.

What has changed is not the intent behind centralization, but the shape of the organization it is now serving. Markets have matured at different speeds. Some face constant digital competition and compressed decision cycles. Others continue to perform steadily without dramatic change. Some have transformed quietly, developing the capability and confidence that were not anticipated when the operating model was designed. Yet many are still expected to function within governance structures built on the assumption of uniform maturity.

This is what it means to mature to the point of pain. An operating model that once enabled growth begins to introduce delay and uncertainty. Not because it is wrong, but because its assumptions no longer hold consistently across the organization.

A useful way to think about modern digital infrastructure is as a shared toolbox.

The toolbox itself should remain central. Platforms, security models, design systems, data standards, and core capabilities all benefit from being owned and governed centrally. This is what creates safety, consistency, and efficiency at scale.

The work carried out with that toolbox, however, varies widely. Some teams are focused on predictable, repeatable execution. Others operate under constant pressure to respond to local signals, competitors, or regulatory nuance. Some need scale and volume. Others need experimentation and speed. Treating these conditions as equivalent is where friction begins to appear. Centralizing the toolbox does not require centralizing every decision about how the tools are used, yet in practice, those two ideas are often conflated.

When progress slows, the platform is frequently blamed. But in most organizations, the platform is not the limiting factor. Modern digital platforms are capable of far more than they are permitted to deliver. The constraint typically sits above the technology, in governance structures, approval mechanisms, and decision rights that were designed for a simpler, more uniform environment.

The effects of this misalignment are familiar. Capability does not mature evenly, leaving some regions confident and self-sufficient while others remain dependent on central execution. Processes lag behind reality, with approval cycles designed for risk avoidance now acting as blunt controls that slow capable teams. Platforms outgrow the rules wrapped around them, leaving functionality unused, not because it is unsafe, but because a differentiated application is not allowed. Performance data often makes the issue clearest: when the fastest-growing or most commercially important markets are also the most constrained, the cause is rarely motivation or skill. Protection remains essential, but when security, compliance, brand, and privacy controls become rigid rather than adaptive, teams compensate through workarounds. Good governance enables autonomy safely. Poor governance reintroduces fragmentation through the back door.

The tension revealed across these patterns is not failure. It is a signal that the organization has outgrown some of its earlier assumptions.

Is your platform constraining your growth?

Decision governance shapes outcomes before technology ever does.

This is usually the point at which decentralization enters the conversation, followed quickly by hesitation.

Decentralization is often associated with loss of control, increased cost, and organizational messiness. In practice, it is rarely a binary choice. It exists on a spectrum and takes different shapes depending on maturity, risk tolerance, and where value is actually created. In some cases, it means allowing capable teams to act without entering a global queue. In others, it means recognizing that different regions, divisions, or product lines operate at different speeds and under different conditions. The mistake is assuming that a single, universal answer must apply everywhere.

Seen this way, decentralization is not about granting freedom. It is about restoring predictability. When decision rights align with capability and accountability, work moves at an expected pace, risk is easier to manage, and confidence in the system increases. When they do not, delay, escalation, and workaround become normalized, and control becomes harder rather than easier to maintain.

AI adds urgency to this conversation, but it does not change its fundamentals. It accelerates existing dynamics. Organizations that already struggle with unclear ownership and slow decision-making will see those weaknesses exposed more quickly. Organizations with clear accountability and well-designed operating models will find that AI amplifies their effectiveness rather than destabilizing it. In that sense, thoughtful decentralization is not a consequence of AI adoption. It is one of the conditions that makes responsible adoption possible.

The real question, then, is not whether to centralize or decentralize. It is how to differentiate intelligently.

What must scale and what must be protected should remain central. Where speed, relevance, and volume create value, decision-making should sit closer to the work. One shared toolbox, clear standards, and autonomy at the point of value creation. This is not a reduction in control. It is a more precise form of it.

Most organizations are not struggling because they chose the wrong model. They are struggling because the right model has outlived the context it was designed for. When key markets are asking for speed, when workarounds become routine, and when AI raises uncomfortable questions about readiness, these are not future concerns. They are present-day signals that the operating model is already being tested.

Which makes the greater risk not choosing the wrong answer, but continuing to operate as though the question does not need to be asked.

To de or not to decentralize.

FAQs

1. Does this mean organizations should decentralize more?

No. The point isn’t decentralization for its own sake. It’s differentiation. What must scale, be protected, and remain consistent should stay central. What requires speed, relevance, and proximity to customers should have decision-making closer to the work. The risk comes from applying a single model uniformly to very different conditions.

2. Is governance the real problem, not technology?

In most cases, yes. Modern platforms are typically capable of far more than organizations allow them to deliver. The real constraint often sits above the technology, in approval cycles, decision rights, and governance models designed for a simpler, more uniform environment. When governance fails to adapt, progress slows, and workarounds emerge.

3. How does AI change this conversation?

AI doesn’t change the fundamentals, it accelerates them. Organizations with clear ownership, adaptive governance, and aligned decision rights will see AI amplify value. Those with slow, unclear, or overly rigid models will see friction and risk surface faster. In that sense, AI is less a cause of change and more a stress test of existing assumptions.